Alexandre Hurr

A 'brief' history of Our Goodman

Alex Hurr (https://alexpaulhurr.wixsite.c...) is a current ethnomusicology MA student at Sheffield University. In this blog piece he has described his lifetime journey of discovery of Child Ballad 274 (Roud 114), Our Goodman. When he is not unearthing the old songs Alex is a sound engineer and co-owner of Axe & Trap (axeandtrapstudios.com) recording studio in Somerset working with acts as diverse as Paraorchestra and We Climb Walls as well as BBC Bristol Introducing

I have a particularly vivid memory of my father playing his A Stack of Steeleye Span CD in the car on very long journeys. Not coming from a particularly musical or even folky household, this would have been some of the very first exposure I had to English folk music. My favourite on the album by far was ‘Four Nights Drunk’ and I would sing along to the recording regularly. I’m sure my dad got a good chuckle by watching 8 year old me cluelessly singing the lyrics about coming home drunk.

As time went on and I discovered more and more about folk music, I would always come back to ‘Four Nights Drunk’, it was a personal favourite that I would love to pull out at the end of sessions or during the walk home after a nice time at the pub. I always enjoyed hearing other versions of the song also, most famously ‘Seven Drunken Nights’ by the Dubliners. One day it struck me, as it so often does to many an avid folkie, ‘I wonder what the oldest version of that song is?’ I thought to myself, ‘and how did it get to the version that I know?’. Thus begun an interesting adventure that I am all too pleased to bring you on…

I’d just like to add a caveat before we start, this is by no means an exhaustive list of versions of this song, nor is it an attempt to provide a list of the best versions, merely those that caught my interest through the chronological discovery of this song. Enjoy!

When digging through sources and old dusty tomes like they do in the films, one important detail was the key to unlocking this journey, ‘Our Goodman’ is the ‘master title’ (as Roud puts it) as ‘Four Nights Drunk’ and he numbers it 114. With this important detail, all points seemed to lead to one source as the first written instance of this song. Of course there’s little doubt that it was sung for a fair few years before but in 1776, David Herd in his book Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads Etc. wrote down the lyrics to the song ‘Our Goodman’. What immediately struck me about this version was how different and yet similar it was to my favourite Span version. Written in a quasi scottish patois, there's no mention of the “good” man being drunk, however, when he does get home his wife corrects him for seeing horse for a bonny milk cow with a saddle on; a sword for a silver (probably?) handed porridge spurtle (this one dates it a little, if I'm honest); a sturdy man for a long-bearded milking maid.

Despite there being about two hundred years between this version and Spans version, the essence of the song has remained remarkably similar. The way in which the story repeats itself but with a few changed words makes it delightfully easy to remember and encouraging for others to sing along to, a detail I love in the song. It's still full of cheeky humour and the final iteration is almost the same! Unfortunately, Herd never left a tune.

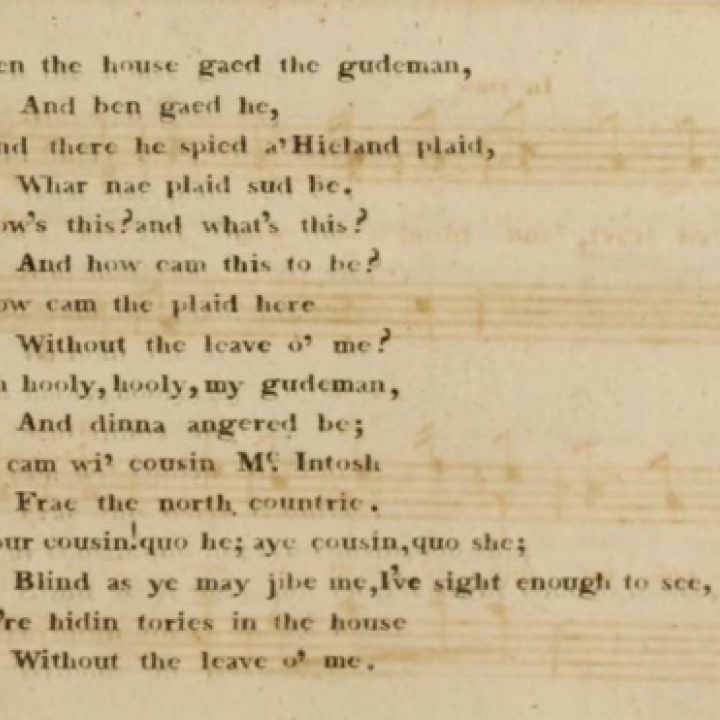

The song appears 50 odd years later in 1823 in Robert Archibald Smith’s book The Scottish Minstrel: A Selection from the Vocal Melodies of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, which includes the song ‘Hame Cam Our Gudeman at E'en’, and this time, a tune! Unbeknownst to me at the time, the song has quite strong roots in Scotland and in this version the Scottish tone is in full force. The name alone is intriguing but the lyrics are not dissimilar to the version collected by David Herd (with references to porridge sticks n’ all) except for the last verse which is well worth a read…

It’s not every day that you read a 200 year old lyric about finding a torie in your house.

The next version I know of was an unbelievably lucky find that happened a few years ago while aimlessly wandering through small parish churches near my parents house in Northamptonshire. In the arched doorway of this one particularly delightful little church near the Spencer Estate was a selection of the usual second-hand books you’d expect to find, Wilber Smith, Delia Smith, Zadie Smith etc… But nestled amongst them was an intriguing number, a few pounds in the jar and I scrambled home to give it a look over. It was The Dialect and Folk-lore of Northamptonshire by Thomas Sternberg, originally printed in 1851. Soon after leafing through it I found, to my utter surprise, an excerpt of ‘Our Goodman’. Though only containing one verse, it was as if I could almost see the song travelling south down the United Kingdom, slowly changing and morphing into different versions. This particular version adorned the song with the addition of the colloquial term ‘Yoicks, bob!’ which I regret to say didn't become a permanent fixture of the song.

Half a century later in 1904 the song appears in Francis J Childs book English and Scottish popular Ballads. In the book, Child includes David Herds version of the song and a broadside version called ‘The Marry Cuckold and Kind Wife’ from Bow Church-Yard in London. However, this is where things get really interesting. The song starts to appear in North America where the collecting and recording of ‘old’ songs starts to really take off. The first instance I’ve been able to find is in the book Traditional Ballads in New England III by Phillips Barry. Recited to Barry on the 30th of March by one D. D. B. in Cambridge, Massachusetts; it replaces long-bearded milk maids with cabbage heads with hair on, what a move! Too crude for an American audience perhaps?

But what about the first recording of the song? With Edisions phonographe just about entering circulation at the turn of the century, there was no chance for the song appearing on anything other than pen and paper up to this point. In 1925, the song ‘Cabbage Head Blues’ was released on an acetate record by Lena Kimbrough in the USA, a fair departure from ‘Hame Cam Our Gudeman at E'en’ you might think! In so many ways yes, but give it a listen. With lines like “whose head is on that pillow, where mine ought to be” and “nothing but a cabbage head your mama gave to me”, it's unmistakably Roud 114. But how can we listen to such an old piece of history? To my utter surprise it's on youtube! Now, granted, it's pretty crackly but that can be forgiven when travelling almost 100 years in the past I like to think.

I was incredibly surprised to find that such an old recording was available so readily like this, expecting to have to dig through the classifieds of some archive in the basement of a rural library, this was incredibly pleasing. But it doesn't end there, a few years later in 1927, Earl Johnson recorded ‘Three Night’s Experience’, here we've got a saddle on a milk-cow, pockets on a bed quilt and a moustache on a cabbage head. And to give this one a listen just head over to Spotify. (right click and open in new window) Knowing that people are still engaging with this song in such an unexpected way was so fascinating, I have no doubt David Herd and perhaps even Smith’s Cousin McIntosh would be proud. It was also becoming clear that “cabbage head” was a North American variant that was going to stick as steadily more recordings were taking place over there.

The first recording that I could find in England did not take place for a fair few years after these however. Apparently some time in the 1930’s the BBC recorded a version of the song called ‘T’owd Chap cam’ ower the Bank’, sung by a gentleman with the name Beckett Whitehead of Delph in Lancashire. But as it was considered “unsuitable” for broadcasting and thus never aired, I’ve not been able to give it a listen myself. Who knows if it's out there somewhere waiting to be dug up…

However, just because there are no recordings to be readily found, it did not stop people continuing to sing the song. We know this because we have several fascinating recordings that took place in the early 50’s that give us rich and powerful evolutions of the song. The first and one of my favourites discovered along this journey, is a series of recordings conducted by Alan Lomax. Released in the year 2000 on a collection called Classic Ballads of Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2, the track ‘The Cuckolds Song (Our Goodman)’ features three singers: Harry Cox, Mary Connors and Colm Keane. I highly recommend listening to Keane’s version which is in Irish Gaelic (I believe). It takes what has typically, up to this point, been quite a satirical song and transforms it into a powerfully lamenting ballad. It's available to buy on Apple Music, otherwise you’ll need to dig through the CD collections in charity shops to get this one.

Ewan MacColl then releases a version of ‘Our Goodman’ as he works his way through the Child Ballads in 1956. To go full circle, this version is the closest recording to those original Scottish versions first written down by Herd and Smith. Though there's some changes, it's enjoyable to hear how MacColl interpreted the most ancient version of the song we have. I particularly enjoy the inclusion of the spoken sections that were originally noted by Smith. You can give it a listen here.

Pete Seeger puts out a very enjoyable and quite typically plucky American Folk style version towards the end of the 50’s. But then things start to get a little strange, my guess would be that as quite a few recordings of the song had been made at this point, people started to push the boat out slightly and, for better or for worse, The Limeliters created the undeniably rockabilly version of Roud 114 in the song ‘Pretty Far Out’. If you have one takeaway from reading this, it should probably be this. With what is quite an imaginative reinvention of the lyrics, the song manages to keep the very same intention as the previouse versions and before you know it you find yourself bopping along, give this version a try at your next sing around and you’ll be the talk of the town.

By quite shocking contrast, just two years later in 1965, John Jacob Niles sings ‘Our Goodman’ on his album My Precarious Life in the Public Domain in a devastatingly morose fashion. From the fun bop of The Limeliters, Niles makes the song feel deeply dark with strained wails and tense strums. A great example of the breadth of emotions that this song can encapsulate, it's fascinating to hear how interpretations can change the tone of a song so drastically.

Pleased with all the discoveries I had made, and more versions of the song than I could ever hope to learn, my timeline brought me back to the familiar ground of Steeleye Span with their release of ‘Four Nights Drunk’. Though it seems that the song's popularity dwindled after this period of relative fame with this release and that of The Dubliners, a few renditions have been recorded since that deserve honourable mentions. The first is Kate Rusby's ‘The Good Man’ which is a delightfully contemporary folk interpretation. In the same year (you’ll be surprised to learn, trust me on this one), a Russian version sung by bard Alexander Dolsky was released. Now, there's quite a few interesting things that have popped up when looking into this version, so much so that I had to ask a Russian friend to help me figure out what was going on. Firstly, it's definitely ‘Our Goodman’, apparently these lyrics are accurate and when translated they absolutely fit into that familiar pattern. However, there are claims circulating that it’s a poem by Robert Burns?! An interesting Scottish link there but not one I’d come across before, but after giving it a listen, I decided that this was more than enough of this song for just a little while…

A big thank you to Renata Tairbekova for her Russian and Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw at the University of Sheffield for the direction.