Whilst it is accepted that “Auld Lang Syne” is attributed to Robert Burns and is recognised far and wide, you may be surprised just how far it has been adopted and adapted across the globe.

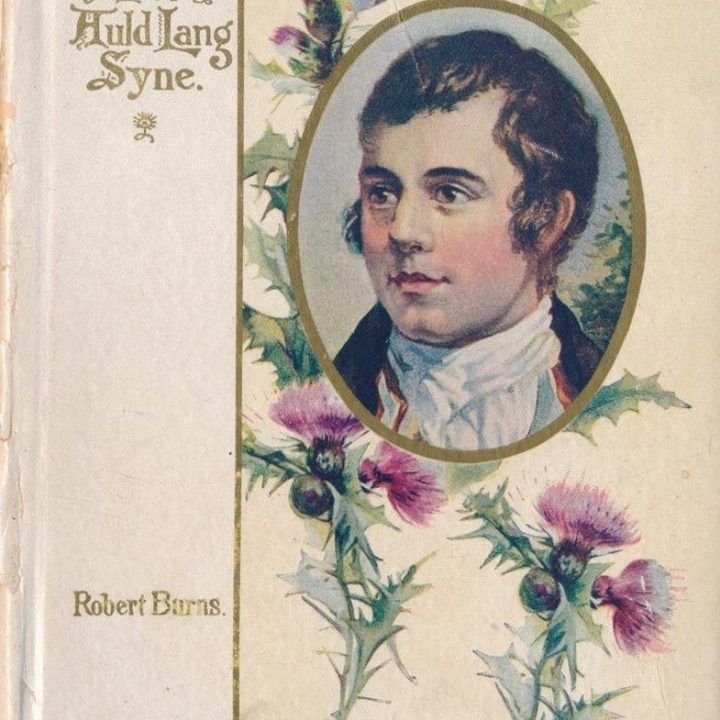

Robert Burns was born on 25th January 1759 in Alloway, Scotland and spent much of his working life in Dumfriesshire working as a labourer and ploughman. Burns was as well known for his gregarious nature, quick wit and love for the ladies as for his musical and literary talents. He was, of course, also an avid collector and re-fashioner of Scottish songs.

On the 17th December 1788 Burns wrote to his friend Mrs Francis Dunlop, “Is not the Scotch phrase, Auld lang syne, exceedingly expressive? There is an old song and tune which has often thrilled through my soul, a song of the olden times, and which has never been in print, nor even in manuscript, until I took it down from an old man’s singing".

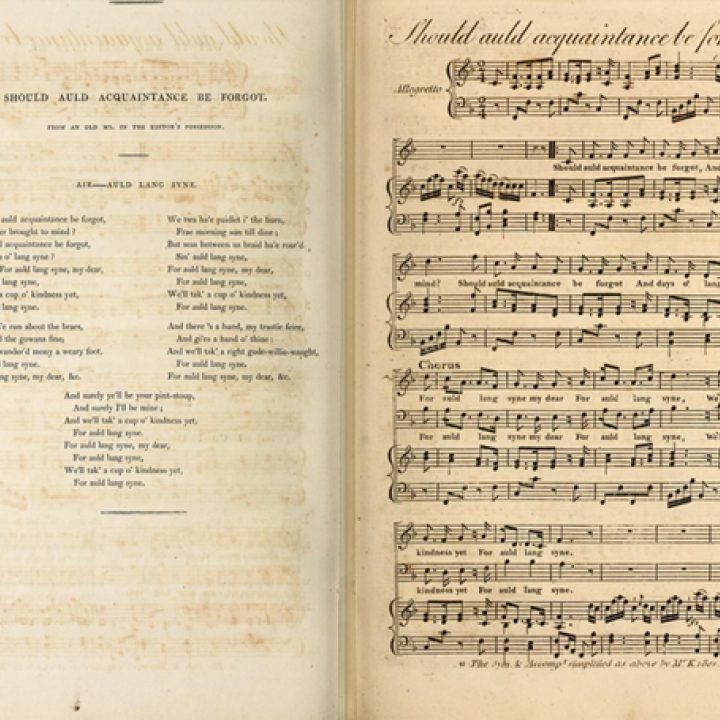

Whilst Burns wrote “Auld Lang Syne” in 1788, the opening line “Should auld acquaintance be forgot” can be traced back long before, into the 16thCentury. He took the existing lyrics and fashioned these into a more universal theme and into the verses and chorus so well recognised today. The music to which the song was put was different to that of today and is a sadder and more reflective piece known as ‘For old long syne my jo’ and appearing in Playford’s Original Scotch Tunes in 1700.

Here is Mairi Campbell singing it.

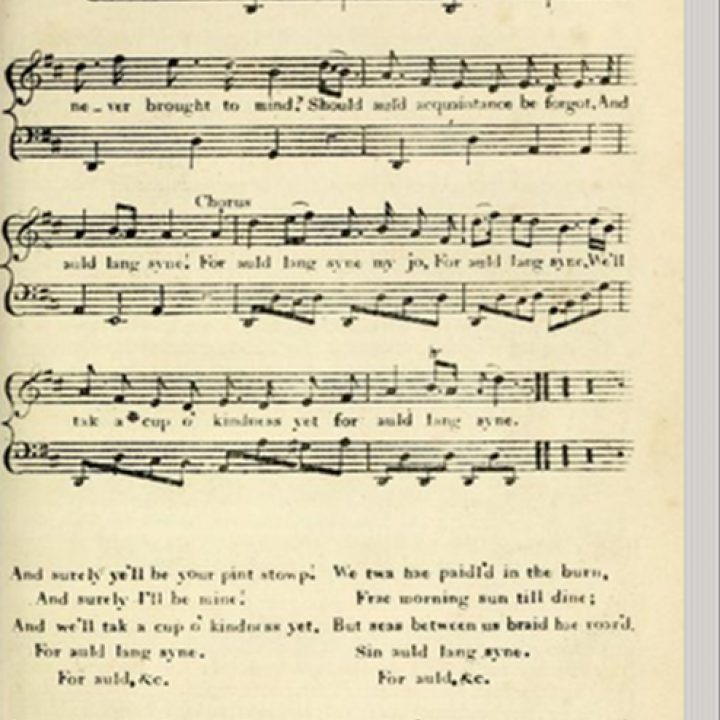

1788 version

In 1799, some four years after Burn’s death the song was published by George Thomson, who had married the lyrics to an old Scottish fiddle tune commonly called the Miller’s Wedding or Miller's Daughter.

Auld Lang Syne (1799 version)

Here's Talisk and Claire Hastings.

This is a tune that Burns was aware of and had actually written another song to called "O Can Ye Labour Lea" and is the tune now commonly associated with Auld Lang Syne. Burns is believed to have written two of the stanzas in the original work and re-shaped the lyrics of some of the original words and chorus, however it is clear that the 1799 version, so recognised today, is a song which, while certainly heavily shaped and influenced by Burns, was not exclusively written by him.

So where in the world do shades of this well kent song appear? Well, possibly in more places than you might imagine.

The Indian Experience

In 1885, Rabindrah Tagore, a prolific and revered Bengali poet / song writer, wrote “Purano Shei Diner Katha” which remains to this day a tremendously popular Bengali song. It utilises the 1799 Thomson tune albeit somewhat adapted in tempo and rhythm, imparting a Bengali flavour in its arrangement. At the age of seventeen a young Tajore had travelled to England for formal schooling and returned to India with a love of Western music, particularly Scottish and Irish. It would be reasonable to assume that it is during this period abroad that he was introduced to Burn’s works, however he did also retain a long term friendship with Scots architect William Geddes which again may have been his introduction to Burn's songs. Tagore’s lyrics were not a translation of Burns' but rather retained the key themes and sentiments of Burns text focussing on friendship, happy times and a longing for their return.

Here is a broad translation of it's lyrics.

"How can you forgo events of the good old days, dear.

The glimpse of each other, spirited chatting, are unforgettable.

Come once more, my friend, come into my heart.

We'll talk about the joy and sorrows to soothe heart.

We've collected flowers at dawn, played and swung a lot

Sang and fluted under the BAKUL tree.

Then happened the separation, alas, we got diverged

When we've got a chance to unite once more, come into my heart"

The French Experience

“Choral de Adieux” is an adaption of Auld Lang Syne, using the original 1799 melody but with rewritten lyrics, focussing on parting and farewells. The lyrics were written by Jesuit Priest Fr Jacques Sevin, the founder of the French scouting movement in 1920 following the singing of Auld Lang Syne at the World Scouts Jamboree. It is popularly sung at New Year in France and is very much part of French tradition and is also still sung by French Scouts.

Here are the translated lyrics.

"Must we leave each other

without a hope

To see each other again some day

Must we leave each other without a hope

A hope of return

It’s only a goodbye, my brothers

It’s only a goodbye,

Yes, we’ll see each other again, my brothers

It’s only a goodbye"

and here is Father Sevin.

The Maldives Experience

The Maldives, a sultanate British Independent territory, gained independence in 1968 at which time it became an Islamic Republic. Whilst there was no evidence that Burns work were published there , it is interesting that in 1948 the Auld Lang Syne tune (1799) version was adopted as the country’s state anthem. A young poet, Mohamed Jameel Didi, having been commissioned to write a new state anthem, composed a poem and set it to a melody he had heard played on the Chief Justice’s clock when it struck at mid-day. It has since been replaced with a new Maldive national anthem.

The Japanese Experience

When public buildings, museums and parks are closing in Japan the strains of “Hotaru no Hikari” (Light of the Fireflies) can be heard being played. Many Japanese people recognise it as one of their own traditional songs, however, whilst the lyrics may focus upon the nostalgia of a Japanese student graduating after a year of hard work, the tune is again that well known 1799 version of the Burns' classic. In the late 1800's Luther Whiting Mason, a Boston music teacher was invited to work with the Japanese Music Study Committee to take the best from Japanese and Western music and poetry and seek to meld these in the production of music suitable for teaching in Japanese schools. These were published between 1881 and 1884 as Elementary School Song Collection books. “Hotaru no Hikari” appears within these books. Since then the song has been accepted and promulgated throughout Japan and can be often heard at school graduations. “Hotaru no hikari” is sung as a song of farewell and departure.

The USA Experience

The introduction of Auld Lang Syne to America is very much a story of diaspora and Scottish emigration, which allowed Scots abroad to remain in contact with their homeland and the cultures and traditions that they had left behind. The formation of St Andrew's and Caledonian societies that sprung up around these communities further promoted and promulgated the culture and songs of Scotland which inevitably would include the songs of Burns. The 1799 version of Burns song, lyrically intact, is sung at New Year in both small and large gatherings across the USA and is accepted as the New Year song. Annually in New York's Times Square over one million revellers turn out to celebrate New Year and to listen and sing along to Guy Lombardo’s Auld Lang Syne being played. Hollywood has also played a significant role in further promulgating Auld Lang Syne both domestically and internationally in the number of movies which have featured renditions.

For those countries which have a significant Scottish diasporic history, particularly Canada and the USA the 1799 tune and lyrics have been preserved and adopted along with traditional Scottish celebrations such as New Year and Burns Nights. These have been reinforced by the various Scottish societies formed around immigrant communities, preserving the ongoing attachment to annual celebrations.

In Japan and China, countries without a significant diasporic history, the introduction of the 1799 tune has been generally as a result of domestic political desires to westernise education and music, met with western desires to spread Christianity and cultural influence. In these countries the lyrics to the song have not just been translated, but have been changed, to produce a re-imagining or reworking to meet political or social ends. This focus on farewell and departure is also common to other countries without a strong diasporic history. The fact that the tune was written in the pentatonic scale, familiar to the indigenous music of these countries may have eased its acceptance and cultural integration.

It is interesting to note the prevailing scouting connection to the tune existing in Poland,

France, Mexico and several other countries. Again, in each of these the 1799 tune has been adopted, however the

lyrics have been separately re-written into songs of farewell. As scouting is

an international movement it is likely that there has been a sharing of music

across these countries, however, this does not fully explain the position as both France

and Mexico sing these songs at New Year also.

The experience in India is somewhat different in that the method of arrival was at least part by way of an indigenous scholar’s visit to England and his friendship with a Scots architect. His subsequent reworking of both tune and lyrics into a popular Indian traditional song is somewhat unique amongst the countries considered here. The reworked song, whilst retaining much of the sentiment of the original, is not associated with Indian celebration or ceremony but rather regarded with a special melancholy and fondness as having been produced by their very own Bard, Rabindrah Tagore.

Historically in countries further afield, with differing cultures the means of introduction of this timeless song has been varied, as has the adaption and the role the song is given. The sentiment expressed in the lyrics of adapted song versions are, however, not wholly dissimilar in sentiment to the original "original" whether from 1788 or 1796. In these countries, similarities in melody and indigenous musical scales assists in more comfortably embedding the song as one which, in time, is considered local to them. Whilst it is not wholly necessary for those who have adopted and adapted Auld Lang Syne into their own musical culture, to understand the history of its complex conception, in many ways they are in fact carrying on Burns rich tradition of borrowing songs and lyrics from long ago and reworking them into something special that touches the heart and renews the spirit.

So, in answer to our question whose Auld Lang Syne is it anyway?

Well.... it is everyone's, no matter who or where you are!

Happy Burns Night.

Here's to the immortal Bard. Slainte

References:

Maldive Royal Family Website

Background to use as national anthem

WEBPAGE

Burns, Auld Lang Syne and New Year,

Future Learn, Glasgow Uni

WEBPAGE

How auld Lang Syne Took Over the World

BBC Overview of song

ARTICLE

The Spreading of Auld Lang Syne and Jakobsens translation Theories

JAI, Hong-Xia

US-China Foreign Language, ISSN 1539-8080

August 2014, Vol. 12, No. 8, 692-697

DISSERTATION

International Journal of Scottish Studies

Burns and the World, Liam McIlvanney

JOURNAL

Japanese Children's Folk Songs before and after Contact with the West

Elizabeth May Journal of the International Folk Music Council

Vol. 11 (1959), pp. 59-65 PAGE 62 Auld lang Syne

JOURNAL

Tagore drew inspiration from Scottish bard for his poem

The Times of India

Newspaper Web Article

TNN | Nov 20, 2011

How Auld Lang Syne switched tunes en route to world domination

Prof Kirsteen McCue, University of Glasgow

December 31, 2015 9.51am GMT

Web Artcle – The Conversation

Robert Burns

from The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature

Drabble, Margaret, 1939-; Stringer, Jenny; Hahn, Daniel (eds).

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007

Book